Oldás és kötés

Oldás és kötés

Hungary, 1963, black and white, 90 mins

Miklós Jancsó’s second feature is, to all practical intents and purposes, his debut, since he has all but disowned his first decade’s output – a large number of documentaries plus a 1958 feature The Bells Have Gone To Rome (A harangok Rómában mentek). Although embryonic glimmerings of Jancsó’s mature style can be discerned towards the end, the dominant influence is clearly Michelangelo Antonioni. If one didn’t already know (since Jancsó has cheerfully admitted it) that La Notte (1961) was a key inspiration, one could easily guess from both the subject matter and treatment of this story of a disillusioned surgeon – the film’s Hungarian title translates as Solution and Bandage.

We first see a gaggle of medical students walking through a park outside the hospital. Two carry books, and one reads aloud while we see the pages of the other, juxtaposing images of fine art with a soundtrack of dry medical terminology – it’s an early example of what would become a characteristic Jancsó technique of editing within the same shot. We eventually meet the protagonist, Dr Ambrus Járom (Zoltán Latinovits, whose resemblance to La Notte’s male protagonist Marcello Mastroianni may not be coincidental). The film’s first third revolves around an operation on a young woman’s heart and lungs, which lays bare the equally complex relationship between Ambrus and his colleagues.

Beforehand, he expresses misgivings about the approach of the senior surgeon known as the Professor (Andor Ajtay). Ambrus takes a strictly Marxist line: surgery in the Professor’s heyday used to be a matter of individual craftsmanship, but it’s since become like a piece of chamber music with various specialists playing together in absolute harmony. Disconcertingly, the operation involves what appears to be genuine surgical footage, adding to the overall tension. There are some striking compositions in this sequence, such as an overhead shot of the white-clad patient being laid down on an equally pristine bed, creating an impression of sterility that’s at odds with the underlying conflict.

But the patient survives primarily because of the Professor’s experience, leading Ambrus into a profound crisis of confidence. A casual remark by a colleague to the effect that doctors’ lifespans are shrinking in parallel with his patients’ improved outlook, coupled with his realisation that he’s spent too long in the stifling hospital environment, convinces him that he needs to escape. But to where?

Up to this point the film has more or less aped Antonioni in its visual treatment and mise-en-scène, placing Ambrus in a variety of largely empty environments (glass, steel, bare white walls) that seem to express an ennui that he can’t quite articulate himself. This impression continues throughout the film’s mid-section, a lengthy party (modelled explicitly on the one in La Notte?) in which Ambrus tries and fails to integrate with his much more laid-back companions – he walks out of a pretentious avant-garde film about dead geese projected to a live jazz accompaniment, and stands aloof from the subsequent discussion, clearly bored and distracted.

While they jabber away, he wanders around, at one point looking idly at his reflection in multiple mirrors, creating a dislocated, fragmented impression mirroring the state of his psyche. Frequent cutaways to a dark-haired woman (Edit Domján) who seems equally disengaged suggests that a rapport is likely to develop, but he eventually walks out without even acknowledging her existence. A café’s back room screens a film featuring both him and the dark-haired woman (Márta), evidently shot in much happier times. She finally joins him, they watch it together and silently reminisce. But when it ends, she mingles freely and easily amongst the others while he remains in the background.

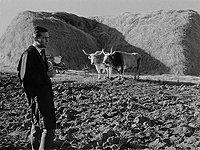

Finally, Ambrus applies for two days’ leave and sets off for the countryside and the film’s final act. It’s here that we see the first stirrings of what would become Jancsó’s own highly individual style: vast, empty plains only occasionally studded with buildings, often shot from a high angle to emphasise the sense of isolation and distance. He encounters old friends from his past life, including a woman, Eta (Mária Medgyesi), who may be a former lover – but is as detached from them as he was from his colleagues and friends. All three conversations between Ambrus and Eta are shot as unbroken deep-focus takes, averaging nearly three minutes, the slow-moving camera constantly alive to the surrounding landscape – another sign of things to come.

But Ambrus feels that he no longer fits. He watches enviously as his father (Béla Barsi) communes with his cattle, and marvels at the way he eschews modern farming technology in favour of horse-drawn ploughs (Ambrus’s hospital is state-of-the-art). During conversations with his father and brother, we get a clearer idea of where he came from: born of peasant stock, he was the beneficiary of state policies dedicated to the advancement of bright people from disadvantaged backgrounds. But this has made his life too easy, his career too meteoric – and if there’s the slightest sign of conflict, he takes the easy option, which is presumably why his various romances foundered.

As with Antonioni, there are no pat answers to a psychological crisis that Ambrus himself admits he can’t articulate. Two brief encounters on the way home, with a hitch-hiking soldier and a kindly station guard, ironically have more value than his other conversations, as they’re based on acts of uncomplicated kindness, with no worries about one’s status or past.

The film’s international title derives from a piece by Béla Bartók, which Ambrus hears on the radio while driving home. In the finale of Cantata Profana: The Nine Enchanted Stags (1930), Bartók draws on a Romanian text depicting nine sons who stray far from home, eventually being transformed into stags. Returning, they find their antlers won’t fit through the door of their father’s house, condemning them to a lifetime’s wandering. If this symbolism is slightly too pat, and the film as a whole has yet to shake off Antonioni’s shadow, it’s equally easy to see why it caused such excitement in Hungarian film circles (winning the Hungarian Critics’ Prize for that year). Even at this early stage, Jancsó had already progressed beyond the merely promising.

- Director: Miklós Jancsó

- Production Manager: József Győrffy

- Screenplay: Miklós Jancsó, Gyula Hernádi, based on the novel by József Lengyel

- Photography: Tamás Somló

- Production Design: Ferenc Ruttka

- Costume Design: Zsuzsa Vicze

- Editor: Zoltán Farkas

- Sound: Ferenc Lohr

- Music: Bálint Sárosi

- Cast: Zoltán Latinovits (Dr. Ambrus Járom), Andor Ajtay (Professor), Béla Barsi (Ambrus’ father), Miklós Szakáts (reader), Gyula Bodrogi (Gyula Kiss), Edit Domján (Márta), Mária Medgyesi (Eta), Gyöngyvér Demjén (young woman); István Avar (Balázs); István Budai (medical student); György Győrffy (artist); Gyula Horváth (Író); János Koltai (Iván Kovács); Vilmos Mendelényi (Katona); László Pethő (artist); József Ross (Uncle Fodor), Mária Sívó (nurse)

DVD Distribution: Clavis Films (France), PAL, no region code.

Picture: Since the box sports images that were clearly blown up from a video source (presumably in the absence of proper promotional stills), I was expecting something much fuzzier than turned out to be the case. Actually, this is an excellent transfer (one of the best I’ve seen of a Jancsó film, in fact), sourced from a very well preserved print with a good range of blacks, whites and intermediate greys – minor spots and scratches are easy to tune out. The aspect ratio is 4:3, and there’s no suggestion that this is anything other than what Jancsó intended – the compositions are sufficiently precise to suggest that any cropping would be obvious.

Sound: The sound isn’t quite as successful, with background hiss throughout and occasional crackle and top-end distortion, though the dialogue comes through clearly enough. It’s entirely plausible that this reflects the original materials – the long take between 1:12:49 and 1:15:56 (the third conversation between Ambrus and Eta) appears to be marred by an insufficiently soundproofed camera.

Subtitles: Despite the French label, both French and English subtitles are provided, and there are no serious issues with the latter (credited to Viktoria Sovak) bar the occasional typo (‘tracktor’, ‘slaugther’) – they’re white, optional and properly synchronised.

Extras: There are no extras.

Links

- Filmtörténet (in Hungarian, but with three video clips)

- Internet Movie Database

- The Torino Film Festival’s page on the film (in English)

- Kinoeye’s excellent overview of Jancsó’s 1960s career briefly mentions Cantata.

- Clavis Films’ page about the DVD (complete with animated menu images).

- DVD available from: Amazon.fr; FNAC, Alapage