As highlighted by my last post, this week sees the launch of the ‘Check the Gate’ festival of recent(ish) Hungarian cinema – and since I’ve now managed to see six-and-a-half out of the seven features being screened, here’s a sneak preview of what’s showing. Given that the festival’s function is to provide a snapshot of what’s been happening in Hungarian cinema over the last half-decade or so, it’s a very impressive selection. All seven films are sharply different in both tone and content, and collectively demonstrate the range of talent that the country has produced in recent years: in virtually all cases, these are first or second features, and most of the filmmakers were born after 1970.

This is what’s showing – for further details on screening times and supporting shorts visit the Curzon Cinemas website.

Kontroll (d. Nimród Antal, 2003) – this wickedly funny and technically assured black comedy is essentially Budapest’s answer to Luc Besson’s Subway (France, 1985), though it’s far less self-conscious and much more entertaining: Antal has already used it as his ticket to Hollywood (where he made motel thriller Vacancy in 2007). Set entirely underground, Kontroll isn’t exactly what you might call an upbeat portrayal of the joys of being a ticket inspector on Budapest’s metro system: the passengers treat them with either indifference, annoyance or open hostility. Small wonder that they while away the time doing less officially-sanctioned things, such as playing chicken on the tracks – but their mettle is put to the test when they get caught up in a murder mystery involving a cowled serial killer pushing passengers in front of approaching trains. Londoners will probably find this subplot especially amusing/alarming, although, sadly, a Tube-based remake is utterly inconceivable (the film opens with a man purporting to represent the Budapest metro, defending his decision to let Antal use it as a location, though this may be as tongue-in-cheek as much of the rest). Lacquer-haired Sándor Csányi is the acting standout as Bulcsú, an inspector with a murky past, and he also pops up as the male lead in…

Kontroll (d. Nimród Antal, 2003) – this wickedly funny and technically assured black comedy is essentially Budapest’s answer to Luc Besson’s Subway (France, 1985), though it’s far less self-conscious and much more entertaining: Antal has already used it as his ticket to Hollywood (where he made motel thriller Vacancy in 2007). Set entirely underground, Kontroll isn’t exactly what you might call an upbeat portrayal of the joys of being a ticket inspector on Budapest’s metro system: the passengers treat them with either indifference, annoyance or open hostility. Small wonder that they while away the time doing less officially-sanctioned things, such as playing chicken on the tracks – but their mettle is put to the test when they get caught up in a murder mystery involving a cowled serial killer pushing passengers in front of approaching trains. Londoners will probably find this subplot especially amusing/alarming, although, sadly, a Tube-based remake is utterly inconceivable (the film opens with a man purporting to represent the Budapest metro, defending his decision to let Antal use it as a location, though this may be as tongue-in-cheek as much of the rest). Lacquer-haired Sándor Csányi is the acting standout as Bulcsú, an inspector with a murky past, and he also pops up as the male lead in…

Just Sex and Nothing Else (Csak szex és más semi, d. Krisztina Goda, 2005) – from the meet-cute opening in which Dóra (Judit Schell) first encounters Tamás (Sándor Csányi) after she’s bustled almost naked out of her lover’s flat, to the final montage of outtakes, this is just as slick and polished a romantic comedy as any of its Hollywood or Richard Curtis-scripted counterparts: it’s no wonder that Goda was quickly snapped up to make the big-budget Children of Glory (Szabadság, szerelem, 2006). It’s been called a Hungarian Bridget Jones’s Diary, which isn’t quite accurate, since the thirtysomething Dóra is more interested in babies than blokes – the title quotes the most enticing bit of the personal ad she ends up placing, which leads to the familiar parade of overly optimistic horrors. No prizes for guessing how it all turns out, but there’s plenty to enjoy along the way, from some genuinely smart dialogue (I’ve never heard avant-garde composer György Kurtág’s name invoked in a one-liner before) and appealing performances, including Zoltán Seress’ accident-prone musician Péter, Károly Gesztesi’s harassed director Paskó, and Antal Czapkó’s Borat-lookalike Turkish waiter Ali, possibly the film’s only genuine romantic. A huge domestic hit, it’s markedly better than the two Polish romantic comedies I’ve seen recently (The Extras/Statyści and Midnight Talks/Rozmowy nocą).

Just Sex and Nothing Else (Csak szex és más semi, d. Krisztina Goda, 2005) – from the meet-cute opening in which Dóra (Judit Schell) first encounters Tamás (Sándor Csányi) after she’s bustled almost naked out of her lover’s flat, to the final montage of outtakes, this is just as slick and polished a romantic comedy as any of its Hollywood or Richard Curtis-scripted counterparts: it’s no wonder that Goda was quickly snapped up to make the big-budget Children of Glory (Szabadság, szerelem, 2006). It’s been called a Hungarian Bridget Jones’s Diary, which isn’t quite accurate, since the thirtysomething Dóra is more interested in babies than blokes – the title quotes the most enticing bit of the personal ad she ends up placing, which leads to the familiar parade of overly optimistic horrors. No prizes for guessing how it all turns out, but there’s plenty to enjoy along the way, from some genuinely smart dialogue (I’ve never heard avant-garde composer György Kurtág’s name invoked in a one-liner before) and appealing performances, including Zoltán Seress’ accident-prone musician Péter, Károly Gesztesi’s harassed director Paskó, and Antal Czapkó’s Borat-lookalike Turkish waiter Ali, possibly the film’s only genuine romantic. A huge domestic hit, it’s markedly better than the two Polish romantic comedies I’ve seen recently (The Extras/Statyści and Midnight Talks/Rozmowy nocą).

Fresh Air (Friss Levegő, d. Ágnes Kocsis, 2006) – a very promising debut that’s already attracted comparisons with Aki Kaurismäki. These aren’t unfair, but it’s also clear that Kocsis and co-director Andrea Roberti have a highly distinctive style of their own, making particularly inspired use of well-judged décor to fill in the gaps left by the long silences between lonely toilet-cleaner Viola (Júlia Nyakó) and her teenage daughter Angéla (Izabella Hegyi), who have far more in common than either is prepared to admit. Although flame-haired Viola is attractive by any standards, she’s painfully shy and introverted (she goes to singles events but freezes out anyone who gets too close) and devotes her life to her work, constructing an inner sanctum between the male and female toilets that’s practically a home from home, where she experiments with aerosol scent combinations. Meanwhile, Angéla is a troubled teen, if a peculiarly lackadaisical one. She’s certainly unhappy with her home, school and social life to the point of running away from home – or rather, making a token nod in that direction as if to make the gesture without committing herself. Much of the film is very funny in a dryly deadpan (yes, Kaurismäkian) way, but the final scenes have a real emotional wrench.

Fresh Air (Friss Levegő, d. Ágnes Kocsis, 2006) – a very promising debut that’s already attracted comparisons with Aki Kaurismäki. These aren’t unfair, but it’s also clear that Kocsis and co-director Andrea Roberti have a highly distinctive style of their own, making particularly inspired use of well-judged décor to fill in the gaps left by the long silences between lonely toilet-cleaner Viola (Júlia Nyakó) and her teenage daughter Angéla (Izabella Hegyi), who have far more in common than either is prepared to admit. Although flame-haired Viola is attractive by any standards, she’s painfully shy and introverted (she goes to singles events but freezes out anyone who gets too close) and devotes her life to her work, constructing an inner sanctum between the male and female toilets that’s practically a home from home, where she experiments with aerosol scent combinations. Meanwhile, Angéla is a troubled teen, if a peculiarly lackadaisical one. She’s certainly unhappy with her home, school and social life to the point of running away from home – or rather, making a token nod in that direction as if to make the gesture without committing herself. Much of the film is very funny in a dryly deadpan (yes, Kaurismäkian) way, but the final scenes have a real emotional wrench.

Hukkle (d. György Pálfi, 2002) – a remarkable calling-card that stands up well even when set against Pálfi’s far more ambitious, lavish and disgusting follow-up Taxidermia. The idea is brilliantly simple: various species that live in, around and even under a Hungarian village are filmed as though for a nature documentary, with the humans given no greater importance than cats, pigs, snakes or beetles (there’s no spoken dialogue, and subtitles are needed only at the very end, when a couple of wedding songs turn out to contain hidden truths). It’s also a murder mystery, albeit a decidedly oblique one, and the first-time viewer is advised to pay as much attention to the background as to anything happening upfront – though this is admittedly not easy when one’s attention is distracted by a pair of swaying porcine testicles the size of watermelons. Given that Pálfi was only just out of film school, it’s an impressively confident piece of work (aurally as well as visually), and even if a couple of the more elaborate CGI flourishes feel a little too much like showing off, he’s clearly shaping up to be one of central Europe’s most distinctive and genuinely original talents. (I discussed Hukkle and Taxidermia in more detail here).

Hukkle (d. György Pálfi, 2002) – a remarkable calling-card that stands up well even when set against Pálfi’s far more ambitious, lavish and disgusting follow-up Taxidermia. The idea is brilliantly simple: various species that live in, around and even under a Hungarian village are filmed as though for a nature documentary, with the humans given no greater importance than cats, pigs, snakes or beetles (there’s no spoken dialogue, and subtitles are needed only at the very end, when a couple of wedding songs turn out to contain hidden truths). It’s also a murder mystery, albeit a decidedly oblique one, and the first-time viewer is advised to pay as much attention to the background as to anything happening upfront – though this is admittedly not easy when one’s attention is distracted by a pair of swaying porcine testicles the size of watermelons. Given that Pálfi was only just out of film school, it’s an impressively confident piece of work (aurally as well as visually), and even if a couple of the more elaborate CGI flourishes feel a little too much like showing off, he’s clearly shaping up to be one of central Europe’s most distinctive and genuinely original talents. (I discussed Hukkle and Taxidermia in more detail here).

Iska’s Journey (Iszka utazása, d. Csaba Bollók, 2007) – at first glance, this comes across as Hungary’s answer to the grim social realism of Ken Loach or the Dardennes brothers (especially the 1999 Palme d’Or winner Rosetta), though much of this portrait of an all too easily exploited teenage waif is at times closer to outright documentary. Lead actress Mária Varga was originally discovered scavenging for scraps of metal in anticipation of the film’s opening scene, and that’s her real-life sibling on screen as well. Shot entirely hand-held, the film follows Iska’s journey from broken home to sleeping rough (after cadging food from a mine canteen, she’s advised to sleep on the slag heap, as it might still be warm), a stint in a state-run orphanage (and a brief, hesitant romance) before ending up on what initially seems like a pleasure-cruise to foreign parts that turns out to be anything but. The film’s often considerable power comes from Iska’s peculiarly convincing blend of streetwise cockiness and underlying innocent naïveté, which somehow remains intact right up to concluding scenes that would otherwise be the last word in bleak despair. Varga is extraordinary in the title role: it’s impossible to tell that she’s female at first, thanks to her close-cropped hair and freckled-urchin face.

Iska’s Journey (Iszka utazása, d. Csaba Bollók, 2007) – at first glance, this comes across as Hungary’s answer to the grim social realism of Ken Loach or the Dardennes brothers (especially the 1999 Palme d’Or winner Rosetta), though much of this portrait of an all too easily exploited teenage waif is at times closer to outright documentary. Lead actress Mária Varga was originally discovered scavenging for scraps of metal in anticipation of the film’s opening scene, and that’s her real-life sibling on screen as well. Shot entirely hand-held, the film follows Iska’s journey from broken home to sleeping rough (after cadging food from a mine canteen, she’s advised to sleep on the slag heap, as it might still be warm), a stint in a state-run orphanage (and a brief, hesitant romance) before ending up on what initially seems like a pleasure-cruise to foreign parts that turns out to be anything but. The film’s often considerable power comes from Iska’s peculiarly convincing blend of streetwise cockiness and underlying innocent naïveté, which somehow remains intact right up to concluding scenes that would otherwise be the last word in bleak despair. Varga is extraordinary in the title role: it’s impossible to tell that she’s female at first, thanks to her close-cropped hair and freckled-urchin face.

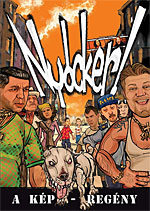

The District! (Nyocker!, d. Áron Gauder, 2004) – my review DVD froze halfway through, just when the main plotline of this Hungarian feature-length animated answer to South Park and Beavis and Butt-Head was getting going. It’s a shame, as I was thoroughly enjoying it: the rotoscope-meets-CGI animation technique was new to me, and Gauder more than matches his US counterparts for unrelieved but shamelessly amusing puerility, this time enhanced with rap interludes (the highly colloquial subtitles certainly ring true). There are also hints of more intelligent social, cultural and political satire – an early classroom scene features the teenage protagonists ignoring their teacher as she struggles to get them interested in ‘Romeo and Juliet’, oblivious of the fact that their own gang rivalries and interracial romances perfectly mirror the play – but I couldn’t tell you if they’re developed to any great extent. Unsurprisingly, it’s also crammed with pop-culture references, many of which are presumably going to go way over the heads of non-Hungarian audiences, though the Matrix-style “bullet-time” shot of a mammoth falling into a pit is a genuine show-stopper – as is the entire subplot about the teens going back millions of years in time to create the conditions for oil to start flowing under their run-down Budapest suburb.

The District! (Nyocker!, d. Áron Gauder, 2004) – my review DVD froze halfway through, just when the main plotline of this Hungarian feature-length animated answer to South Park and Beavis and Butt-Head was getting going. It’s a shame, as I was thoroughly enjoying it: the rotoscope-meets-CGI animation technique was new to me, and Gauder more than matches his US counterparts for unrelieved but shamelessly amusing puerility, this time enhanced with rap interludes (the highly colloquial subtitles certainly ring true). There are also hints of more intelligent social, cultural and political satire – an early classroom scene features the teenage protagonists ignoring their teacher as she struggles to get them interested in ‘Romeo and Juliet’, oblivious of the fact that their own gang rivalries and interracial romances perfectly mirror the play – but I couldn’t tell you if they’re developed to any great extent. Unsurprisingly, it’s also crammed with pop-culture references, many of which are presumably going to go way over the heads of non-Hungarian audiences, though the Matrix-style “bullet-time” shot of a mammoth falling into a pit is a genuine show-stopper – as is the entire subplot about the teens going back millions of years in time to create the conditions for oil to start flowing under their run-down Budapest suburb.

Dealer (d. Benedek Fliegauf, 2004) – for those lamenting the absence of anything by Béla Tarr in the festival, this comes closest to his worldview. On paper, this depiction of the last 24 hours in the life of an unnamed drug dealer sounds close kin to Iska’s Journey (or Nicholas Winding Refn’s Pusher films) as it follows him visiting his various clients (many of whom are friends or lovers), briefly acquiring a daughter along the way. Refusing to moralise, he spends much of the time trying to maintain a cool detachment from events, though the final scene makes clear that this is ultimately impossible. But realism is the last thing on Fliegauf’s mind as he shoots each scene with a slowly circling camera, only gradually revealing key details. He was also a major contributor to the soundtrack, one of the most brilliantly-designed that I’ve heard in ages. Influenced by, amongst others, the band Portishead, it’s as eloquent and rigorous as the visuals, somehow contriving to have the same faint, breathy three-note motif repeated throughout the entire running time without ever seeming redundant. Dealer certainly isn’t for everyone, and there are times when content fights a losing battle with style, but Fliegauf is definitely a talent to watch.

Dealer (d. Benedek Fliegauf, 2004) – for those lamenting the absence of anything by Béla Tarr in the festival, this comes closest to his worldview. On paper, this depiction of the last 24 hours in the life of an unnamed drug dealer sounds close kin to Iska’s Journey (or Nicholas Winding Refn’s Pusher films) as it follows him visiting his various clients (many of whom are friends or lovers), briefly acquiring a daughter along the way. Refusing to moralise, he spends much of the time trying to maintain a cool detachment from events, though the final scene makes clear that this is ultimately impossible. But realism is the last thing on Fliegauf’s mind as he shoots each scene with a slowly circling camera, only gradually revealing key details. He was also a major contributor to the soundtrack, one of the most brilliantly-designed that I’ve heard in ages. Influenced by, amongst others, the band Portishead, it’s as eloquent and rigorous as the visuals, somehow contriving to have the same faint, breathy three-note motif repeated throughout the entire running time without ever seeming redundant. Dealer certainly isn’t for everyone, and there are times when content fights a losing battle with style, but Fliegauf is definitely a talent to watch.