Hideg napok.

Hideg napok.

Hungary, 1966, black and white, 96 mins.

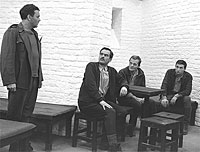

It’s hard to fault the title: virtually every scene in András Kovács’ powerful film is either set outdoors in snow that audibly crunches underfoot, or in a white-walled prison cell where central heating clearly isn’t a top priority. The latter is occupied by four former members of the Hungarian army, awaiting trial in connection with various atrocities committed four years earlier, in 1942, when over three thousand Serbs and Jews from the town of Novi Sad (recently annexed to Hungary) were massacred in legally dubious circumstances. The chill is further accentuated by the occasional use of the spare, almost skeletal third movement of Béla Bartók’s ‘Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta’ (some fourteen years in advance of Stanley Kubrick co-opting it for The Shining) and an early shot of a hole being blasted in the iced-over Danube. Kovács is too discreet to show exactly what it’s being used for, but the sight of civilians shivering on the bank, planks being laid to to the edge of the hold, a pile of discarded clothes and armed guards being given their orders leaves us in little doubt.

Naturally, the cell’s inmates are anxious to minimise or deny their involvement in the above (as Tarpataki puts it “nobody is better or worse, just more or less fortunate”), but as they argue amongst themselves, a much clearer picture emerges, aided by Rashomon-style flashbacks from their multiple viewpoints). The most senior prisoner, Major Büky (Zoltán Latinovits), considers himself more of a victim than a participant, since his wife Rózsa was caught up in the round-ups of prisoners and subsequently vanished. Throughout Büky’s testimony, he is at pains to stress his essential decency, and that of his wife – brought up to be anti-Semitic, she nonetheless became friends with her Jewish landlady Edit. He is convinced that Rózsa is still alive, unconvincingly explaining that women have a good sense of danger and know when to take evasive action. He also cites the disappearance of her suitcase as evidence that she pre-emptively fled: despite increasing indications to the contrary, he refuses to believe that Hungarian soldiers could ever be guilty of looting.

Naturally, the cell’s inmates are anxious to minimise or deny their involvement in the above (as Tarpataki puts it “nobody is better or worse, just more or less fortunate”), but as they argue amongst themselves, a much clearer picture emerges, aided by Rashomon-style flashbacks from their multiple viewpoints). The most senior prisoner, Major Büky (Zoltán Latinovits), considers himself more of a victim than a participant, since his wife Rózsa was caught up in the round-ups of prisoners and subsequently vanished. Throughout Büky’s testimony, he is at pains to stress his essential decency, and that of his wife – brought up to be anti-Semitic, she nonetheless became friends with her Jewish landlady Edit. He is convinced that Rózsa is still alive, unconvincingly explaining that women have a good sense of danger and know when to take evasive action. He also cites the disappearance of her suitcase as evidence that she pre-emptively fled: despite increasing indications to the contrary, he refuses to believe that Hungarian soldiers could ever be guilty of looting.

Not to be outdone, Lieutenant Tarpataki (Iván Darvas) tells an anecdote about an arbitrary arrest and detention procedure in which market sellers were rounded up, vetted by one of their customers, and the ones she didn’t recognise were taken away and presumably killed: he claims he regrets his passivity in the face of clear breaches of military convention. He also plays down the explosions on the ice, claiming that there are plenty of legitimate reasons for making holes. Ensign Pozdor (Tibor Szlyági) is obsessed with where the death statistics came from – 3,309 alleged victims, but who counted them? And how could they accurately say that 299 were “of advanced age”? At one point, when confronted with increasingly clear evidence of his own guilt, Pozdor seeks to play it down by saying that it’s wrong for him to have been singled out, since everyone in his unit was just as guilty of committing atrocities. By reducing the victims to mere numbers, he’s cynically (or possibly unconsciously) diminishing their status as human beings.

Not to be outdone, Lieutenant Tarpataki (Iván Darvas) tells an anecdote about an arbitrary arrest and detention procedure in which market sellers were rounded up, vetted by one of their customers, and the ones she didn’t recognise were taken away and presumably killed: he claims he regrets his passivity in the face of clear breaches of military convention. He also plays down the explosions on the ice, claiming that there are plenty of legitimate reasons for making holes. Ensign Pozdor (Tibor Szlyági) is obsessed with where the death statistics came from – 3,309 alleged victims, but who counted them? And how could they accurately say that 299 were “of advanced age”? At one point, when confronted with increasingly clear evidence of his own guilt, Pozdor seeks to play it down by saying that it’s wrong for him to have been singled out, since everyone in his unit was just as guilty of committing atrocities. By reducing the victims to mere numbers, he’s cynically (or possibly unconsciously) diminishing their status as human beings.

Throughout their testimonies, blame is firmly placed on General Feketehalmy-Czeydner and Colonel Grassy, the former given to patriotic rabble-rousing (“I shall not abide cowardice! More zeal! More fighting spirit!”), the latter favouring largely indiscriminate slaughter: at one point, Grassy orders an entire group of suspects to be killed because the forty partisans he’s after are presumably among them. To sidestep justified suspicions that they’re crudely opting for the (concurrent) Nuremberg defence that only the people giving the orders were to blame, the conveniently dead Corporal Dorner (István Avar) becomes the primary scapegoat, being shown drunkenly killing an innocent (Jewish) electrician and his son. Grassi allegedly refuses to take any action, telling Büky that when Germans are invading, concern for individual Jews is misplaced, and that punishing men for trivial infractions would demoralise them.

Throughout their testimonies, blame is firmly placed on General Feketehalmy-Czeydner and Colonel Grassy, the former given to patriotic rabble-rousing (“I shall not abide cowardice! More zeal! More fighting spirit!”), the latter favouring largely indiscriminate slaughter: at one point, Grassy orders an entire group of suspects to be killed because the forty partisans he’s after are presumably among them. To sidestep justified suspicions that they’re crudely opting for the (concurrent) Nuremberg defence that only the people giving the orders were to blame, the conveniently dead Corporal Dorner (István Avar) becomes the primary scapegoat, being shown drunkenly killing an innocent (Jewish) electrician and his son. Grassi allegedly refuses to take any action, telling Büky that when Germans are invading, concern for individual Jews is misplaced, and that punishing men for trivial infractions would demoralise them.

It’s the fourth and most militarily junior cellmate, Corporal Szabó, who is the most honest, presumably because he lacks either the authority or the political nous to transfer blame. Also, as an underling, he was compelled to participate in the massacre because the alternative would have been near-certain death for himself. While he also uses the “only obeying orders” defence, he knows that it has much more justification in his case, and can therefore go into the kind of detail that his colleagues have been deliberately shying away from – in the process revealing information about the near-certain fate of Büky’s wife that causes Büky’s previously controlled, quasi-aristocratic demeanour to suddenly vanish. This explosion of violent rage is doubly revealing, simultaneously exposing Büky’s total selfishness (having previously regarded the fate of thousands with something close to equanimity) and demonstrating how even someone as outwardly quiet, bookish and ‘civilised’ as him can be goaded into committing atrocities given a convincing enough excuse.

It’s the fourth and most militarily junior cellmate, Corporal Szabó, who is the most honest, presumably because he lacks either the authority or the political nous to transfer blame. Also, as an underling, he was compelled to participate in the massacre because the alternative would have been near-certain death for himself. While he also uses the “only obeying orders” defence, he knows that it has much more justification in his case, and can therefore go into the kind of detail that his colleagues have been deliberately shying away from – in the process revealing information about the near-certain fate of Büky’s wife that causes Büky’s previously controlled, quasi-aristocratic demeanour to suddenly vanish. This explosion of violent rage is doubly revealing, simultaneously exposing Büky’s total selfishness (having previously regarded the fate of thousands with something close to equanimity) and demonstrating how even someone as outwardly quiet, bookish and ‘civilised’ as him can be goaded into committing atrocities given a convincing enough excuse.

Unlike Zoltán Fábri’s near-contemporaneous Twenty Hours (Húsz óra, 1965), where the portrait gradually assembled by the flashbacks indicated a community of sharply divergent views and opinions, here Kovács uses four very different testimonies to paint what is ultimately a wholly coherent picture of the same event, with each man bearing equal moral guilt for what happened – if they weren’t actual participants, like Szabó, they could have taken some kind of action to stop or minimise it. The film’s dominant message (expressed unusually bluntly by the elliptical standards of mid-1960s Hungarian cinema), that for evil to triumph it is necessary for good men to do nothing, could just as easily be transferred to any number of contentious political and military situations. Kovács was clearly challenging his Hungarian audience to think about this and similar events, many of which would have happened well within the lifetimes of a mid-1960s audience.

Unlike Zoltán Fábri’s near-contemporaneous Twenty Hours (Húsz óra, 1965), where the portrait gradually assembled by the flashbacks indicated a community of sharply divergent views and opinions, here Kovács uses four very different testimonies to paint what is ultimately a wholly coherent picture of the same event, with each man bearing equal moral guilt for what happened – if they weren’t actual participants, like Szabó, they could have taken some kind of action to stop or minimise it. The film’s dominant message (expressed unusually bluntly by the elliptical standards of mid-1960s Hungarian cinema), that for evil to triumph it is necessary for good men to do nothing, could just as easily be transferred to any number of contentious political and military situations. Kovács was clearly challenging his Hungarian audience to think about this and similar events, many of which would have happened well within the lifetimes of a mid-1960s audience.

- Director: András Kovács

- Screenplay: András Kovács, based on the novel by Tibor Cseres

- Photography: Ferenc Szécsényi

- Production Design: Béla Zeichan

- Costume Design: Zsazsa Lázár

- Sound: Gábor Erdélyi

- Editing: Mária Daróczy

- Production Manager: Ottó Föld

- Cast: Zoltán Latinovits (Major Büky), Iván Darvas (Lieutenant Tarpataki), Tibor Szilágyi (Ensign Pozdor), Ádám Szirtes (Corporal Szabó), Margit Bara (Rózsa), Éva Vass (Edit), Mari Szemes (Milena), Irén Psota (Betti), Teri Horváth (Pénztárosnö), István Avar (Corporal Dorner), Tamás Major (Colonel Grassy), János Zách (General Feketehalmy-Czeydner), János Koltai (Adolf Gottlieb), György Bárdy, István Bujtor, Nándor Tomanek, Edit Soós

- Production Company: MAFILM Stúdió 1

Links

- The Filmtörténet entry includes a video extract (unsubtitled Hungarian).

- Internet Movie Database