Tízezer nap.

Tízezer nap.

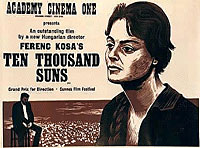

Hungary, 1965/67, black and white, 110 mins.

One of the most impressive Hungarian directorial debuts, Ten Thousand Suns offers clinching proof that Miklós Jancsó wasn’t the only mid-1960s master routinely offering breathtaking widescreen compositions featuring hundreds of men and horses. Shot by Sándor Sára, then well on his way to cementing his reputation as one of Hungarian cinematography’s greatest visual artists, the film routinely throws up stunning shots: mass wheat scything, dozens of horses crossing a bridge to market (followed shortly afterwards by train wagons crossing the same bridge heading in the opposite direction, a neat visual gag on technological progress), prisoners doing hard labour on a rocky hillside, numerous public festivities crammed with local colour. The aesthetic impact alone makes it’s easy to see why this once had a considerable international reputation, even achieving a commercial release in Britain.

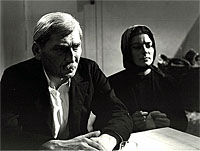

Another reason for its acclaim outside Hungary may be that while it tackles similar material to Zoltán Fábri’s Twenty Hours (Húsz óra, 1965), it does so in the much more immediately accessible form of a three-decade family saga (the period alluded to by the title adds up to just over 27 years) which spans the pre-war era through to the János Kádár’s so-called ‘goulash communism’ of the 1960s. We watch the former peasants István Széles (Tibor Molnár), his wife Juli (a wonderfully expressive Gyöngyi Bürös, her silences as eloquent her sparse dialogue) and their friend Bánó Fülöp (János Koltai) negotiating all the pitfalls that history strews in their path, not always with complete success. Though long-term friends, István and Bánó are politically poles apart: Bánó is the local Communist activist, organising a trade union and enthusiastically implementing agricultural reform on the local collective farm. By contrast, István consciously shuns identification with a particular line, and while this makes him a much more clear-sighted observer of communism’s drawbacks, it’s not without considerable hardship along the way, including a long spell in prison – though he also refuses to side with the rebels of 1956, since they also stand in the way of his landowning ambitions. (More specifically, he refuses to shoot Bánó, despite the latter now being firmly established as his ideological ‘enemy’).

Another reason for its acclaim outside Hungary may be that while it tackles similar material to Zoltán Fábri’s Twenty Hours (Húsz óra, 1965), it does so in the much more immediately accessible form of a three-decade family saga (the period alluded to by the title adds up to just over 27 years) which spans the pre-war era through to the János Kádár’s so-called ‘goulash communism’ of the 1960s. We watch the former peasants István Széles (Tibor Molnár), his wife Juli (a wonderfully expressive Gyöngyi Bürös, her silences as eloquent her sparse dialogue) and their friend Bánó Fülöp (János Koltai) negotiating all the pitfalls that history strews in their path, not always with complete success. Though long-term friends, István and Bánó are politically poles apart: Bánó is the local Communist activist, organising a trade union and enthusiastically implementing agricultural reform on the local collective farm. By contrast, István consciously shuns identification with a particular line, and while this makes him a much more clear-sighted observer of communism’s drawbacks, it’s not without considerable hardship along the way, including a long spell in prison – though he also refuses to side with the rebels of 1956, since they also stand in the way of his landowning ambitions. (More specifically, he refuses to shoot Bánó, despite the latter now being firmly established as his ideological ‘enemy’).

Kósa parallels this central narrative with a vivid portrait of the lot of workers over this period. Before the war, István, Juli, Bánó and their peasant cohorts live in extreme poverty, effectively slaves to the local landowners and all their actions are shown to have moral consequences above and beyond their notional illegality – for instance, stealing straw from the pigs to use as fuel on New Year’s Eve means that the piglets will be found frozen to death the following morning (in one of many quirky touches that separate this film from one of Jancsó’s more earnest parables, the miscreants are ordered to apologise to the surviving pigs). The potato is the staple diet, and not just as food – Bánó manages to get one to power a radio. A strike leads to a confrontation between those seeking higher wages and those who point out that they’ll starve without work, though the latter end up ritually humiliated by being tied to upended wheelbarrows and having dirt thrown in their faces.

Kósa parallels this central narrative with a vivid portrait of the lot of workers over this period. Before the war, István, Juli, Bánó and their peasant cohorts live in extreme poverty, effectively slaves to the local landowners and all their actions are shown to have moral consequences above and beyond their notional illegality – for instance, stealing straw from the pigs to use as fuel on New Year’s Eve means that the piglets will be found frozen to death the following morning (in one of many quirky touches that separate this film from one of Jancsó’s more earnest parables, the miscreants are ordered to apologise to the surviving pigs). The potato is the staple diet, and not just as food – Bánó manages to get one to power a radio. A strike leads to a confrontation between those seeking higher wages and those who point out that they’ll starve without work, though the latter end up ritually humiliated by being tied to upended wheelbarrows and having dirt thrown in their faces.

Following the war, whose passage and outcome is efficiently conveyed by newsreels and shots of black-shrouded women in mourning laying candles on tombstones, a new government decrees that the land belongs to those who need it. This leads to scenes that echo one of the flashbacks in Twenty Hours, as over-excited peasants pre-emptively raid a grain store, a politician pleading with them to stop and wait as the grain will soon be theirs anyway. A massed celebration includes a speed-eating contest reminiscent of the ones in György Pálfi’s grotesque Taxidermia (2006) as well as mass wrestling, a twilight dance around a bonfire, and a merry-go-round (an iconic shot for Hungarian cinema ever since Zoltán Fábri made one the centrepiece of his breakthrough film Merry-Go-Round/Körhinta in 1955).

Following the war, whose passage and outcome is efficiently conveyed by newsreels and shots of black-shrouded women in mourning laying candles on tombstones, a new government decrees that the land belongs to those who need it. This leads to scenes that echo one of the flashbacks in Twenty Hours, as over-excited peasants pre-emptively raid a grain store, a politician pleading with them to stop and wait as the grain will soon be theirs anyway. A massed celebration includes a speed-eating contest reminiscent of the ones in György Pálfi’s grotesque Taxidermia (2006) as well as mass wrestling, a twilight dance around a bonfire, and a merry-go-round (an iconic shot for Hungarian cinema ever since Zoltán Fábri made one the centrepiece of his breakthrough film Merry-Go-Round/Körhinta in 1955).

But the euphoria quickly gives way to disgruntlement: Bánó asserts that the more one gives, the happier one is, but when he seeks to put this notion into practice by requisitioning some of István’s grain for the benefit of poorer community members, István is unimpressed by the argument that it properly belongs to the people and resolves to steal it back, an action that leads to the death of his man-mountain accomplice Mihály (previously seen as a champion speed-eater and wrestler) and hard labour for István himself. When he returns, he finds his son grown up (and now played by András Kozák, a regular lead in Jancsó’s films) and evidence of the encroachment of progress – Juli tells him that the women wear nylon now, and the peasant houses are now dwarfed by much more modern buildings. This sequence of the film delights in juxtaposing the ancient and the modern: a lovely lyrical sequence sees a session of ploughing accompanied by the slow movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, a forest is mysteriously populated with riderless bicycles, and a trip to the beach reveals a bizarre juxtaposition of costume styles from modern bathing costumes to traditional Hungarian male headgear.

But the euphoria quickly gives way to disgruntlement: Bánó asserts that the more one gives, the happier one is, but when he seeks to put this notion into practice by requisitioning some of István’s grain for the benefit of poorer community members, István is unimpressed by the argument that it properly belongs to the people and resolves to steal it back, an action that leads to the death of his man-mountain accomplice Mihály (previously seen as a champion speed-eater and wrestler) and hard labour for István himself. When he returns, he finds his son grown up (and now played by András Kozák, a regular lead in Jancsó’s films) and evidence of the encroachment of progress – Juli tells him that the women wear nylon now, and the peasant houses are now dwarfed by much more modern buildings. This sequence of the film delights in juxtaposing the ancient and the modern: a lovely lyrical sequence sees a session of ploughing accompanied by the slow movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, a forest is mysteriously populated with riderless bicycles, and a trip to the beach reveals a bizarre juxtaposition of costume styles from modern bathing costumes to traditional Hungarian male headgear.

The film’s final sequences reveal Kósa’s ultimate thesis, as father and son are explicitly contrasted despite sharing the same name. István senior is a traditionalist, raised as part of a hierarchy, and consequently his notion of ambition is to rise up to the top – or at least to a level where he can ensure a life of comfort and plenty. He’s paralleled with King Lear, whose decision to give up his land resulted in his decline and death. But István junior is a child of the postwar era, raised in a very different environment where the physical and social needs of the community come before individual desires – and therefore, Kósa implies, a model citizen of a new socialist Hungary where theory and practice can finally become one.

The film’s final sequences reveal Kósa’s ultimate thesis, as father and son are explicitly contrasted despite sharing the same name. István senior is a traditionalist, raised as part of a hierarchy, and consequently his notion of ambition is to rise up to the top – or at least to a level where he can ensure a life of comfort and plenty. He’s paralleled with King Lear, whose decision to give up his land resulted in his decline and death. But István junior is a child of the postwar era, raised in a very different environment where the physical and social needs of the community come before individual desires – and therefore, Kósa implies, a model citizen of a new socialist Hungary where theory and practice can finally become one.

- Director: Ferenc Kósa

- Screenplay: Ferenc Kósa, Sándor Csoóri, Imre Gyöngyössy

- Photography: Sándor Sára

- Production Design: József Romvári

- Sound: György Pintér

- Editing: Ferencné Szécsényi

- Music: András Szöllősy

- Production Manager: József Bajusz

- Cast: Tibor Molnár (István Széles), Gyöngyi Bürös (Juli), András Kozák (István Széles junior), János Koltai (Bánó Fülöp), Ida Siménfalvy (Széles’ mother), János Rajz (Balogh), János Siménfalvy (Uncle Sándor), Anna Nagy (Mihály’s wife), Nóra Káldi (policeman’s wife), Kornélia Sallai (Bánó’s wife), László Ferencz (gypsy), István Szilágyi (referee), Péter Haumann (policeman), László Nyers (Mihály Csere), István Széles, Mihály Papp

- Production Company: MAFILM

Links

- The Filmtörténet entry includes a video extract (in unsubtitled Hungarian).

- Internet Movie Database

Anything remotely compared to Taxidermia, which is one of my favorite films, piques my interest.

Well, aside from the speed-eating contest, there’s not a huge amount in common – though I bet György Pálfi has seen it.