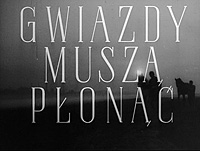

Gwiazdy muszą płonąć

Gwiazdy muszą płonąć

Poland, 1954, black and white, 64 mins

Most filmographies claim that Man on the Tracks (Człowiek na torze, 1956) is Andrzej Munk’s first feature, yet two earlier entries in his filmography could also qualify, and not just because of their length. The 64-minute The Stars Must Burn, which Munk co-directed with Witold Lesiewicz, is still nominally a documentary – it’s based on actual events and was cast with real miners – but the techniques of fiction filmmaking are far more apparent than in his earlier work, and the end result is just as effective as a piece of drama.

The film’s three-act structure draws on two stories: the rediscovery of long-abandoned but still potentially productive shafts in a Silesian coal mine (which form the first and third acts) and the mid-point story of old Górecki, a miner who tends the pit ponies but is faced with redundancy. There’s a wraparound bookend that harks back to the overt didacticism of the Socialist Realist period – the title refers to the practice of erecting illuminated stars at the highest point of the mine, which when lit reveal to the world that the miners have achieved their production quota – but Munk and Lesiewicz are clearly more interested in the experiences of the miners as individuals.

Munk’s episode is the one about the abandoned mineshaft, and is much the most successful. This is because he uses its straightforward narrative as an excuse for blending some impressively atmospheric photography with near-constant suspense, as the miners are faced with the ever-present dangers of rock falls and gas-fuelled explosions, and are linked to the surface only by a decidedly unreliable Ariadne’s thread of a phone cable.

The reason why they’re taking such risks is that they’re desperately trying to save the Zagorze mine from closure. In the opening scenes, we see the Polish Office of National Statistics compiling damning figures about its output, accompanied by a lecture about what a 2% shortfall means for the country as a whole (a message underscored by a brief vignette about a near-disaster at the Borek steelworks, forced to run on inferior coke). Formerly Stakhanovite miners like Parolik are considering their positions, but his colleagues Kowol, Kania and Mazur are made of sterner stuff, especially after Kowol uncovers historical evidence that the Zagorze mine used to be rather more extensive than the modern version.

The segment where they start exploring the old mine shaft provides an excuse for the film’s most atmospheric photography . Particularly striking is the shot of the miners navigating the now flooded shaft, the gases settled a few inches above the surface of the water, their journey conducted in near silence as Jan Krenz’s score thins out to a single bass woodwind.

A third of the way through, after the first attempt at uncovering the old seam fails, the scene changes to a different mine in Milkowice, a much smaller operation that’s the last Polish mine to employ pit ponies. Lesiewicz’s middle episode is much more leisurely than Munk’s, and much more prone to cuteness (the scene where the horse Andalusia demonstrates her counting skills) and pathos (the ponies’ days are numbered, as are those of old Górecki), though there’s an effectively lyrical scene when Górecki and his young colleague Tuleja take the ponies out to run free in a nearby field, the accompanying woodwind now in a higher register.

And then we return to Zagorze and another attempt at exploring the old seam, this time with better equipment. But, as the film makes clear, mines have hidden dangers that no amount of technology can entirely defeat – a two-hour oxygen supply seems generous until one is trapped underground. Munk generates a fair amount of suspense from scenes such as the one in which a naked flame is used to test for gas, and the period when the phone goes dead for several minutes, with only the surface operator’s voice echoing through the empty chambers. With voiceover kept to a minimum, this part of the film is almost pure drama, and it’s only the concluding section that sets the miners’ success against the achievements of Polish coalmining as a whole that reminds the viewer that it’s still a documentary at base. The dividing line between fact and fiction would be blurred even more by Munk’s next feature, the mountain rescue drama Men of the Blue Cross (Błękitny krzyż, 1955).

- Directors: Andrzej Munk, Witold Lesiewicz

- Script: Witold Lesiewicz, Andrzej Munk, in collaboration with Karol Małcużyński

- Camera: Zbigniew Raplewski, Romuald Kropat

- Editing: Maria Orłowska, Jadwiga Zajiček, Halina Kubik

- Narration: Karol Małcużyński

- Voice-Over: Gustaw Holoubek

- Sound: Zbigniew Wolski

- Music: Jan Krenz

- Production Manager: Wilhelm Hollender

- Production Company: Wytwórnia Filmów Dokumentalnych (Documentary Film Studio)

The film is included on PWA’s Polish School of the Documentary: Andrzej Munk double-DVD set (Region 0 PAL). The source print is one of the better ones on these discs, with some damage around reel changes, but otherwise commendably well preserved. A wide contrast range provides a good showcase for the atmospheric cinematography. The sound is equally fine. Aside from two points in which one or two sentences are inexplicably left untranslated, the English subtitles are perfectly acceptable, rendering onscreen text as well as spoken content. Online commentary is provided by this Culture.pl overview of Munk’s career, which briefly mentions The Stars Must Burn.