Człowiek na torze

Człowiek na torze

Poland, 1956, black and white, 80 mins

Notwithstanding the fact that The Stars Must Burn (Gwiazdy muszą płonąć, 1954) and Men of the Blue Cross (Błękitny krzyż, 1955) were arguably closer to drama than documentary, Man on the Tracks is generally recognised as Andrzej Munk’s first fiction feature. And in many ways this is appropriate, as his approach here represents a far sharper break with the Social Realist propaganda films of the past than anything he had previously attempted. Although he had gradually been shifting attention from collective to individual achievements, up to now his stories had been told by a single voice, usually in the form of an omniscient narrator. Here, though, the same events are recounted from three different perspectives, an approach presumably inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) – and by the end, our initial impressions of a seemingly straightforward event have been turned upside down.

A brief series of opening scenes sets up the situation: a passenger train driven by newly-qualified engineer Stanisław Zapora is forced to brake hard, after a man is spotted on the tracks frantically waving. The train collides with the man, killing him instantly. He is rapidly identified as Władysław Orzechowski, a former railway engineer who was widely seen as being uncooperative and divisive. Once it’s established that one of the lamps in a nearby signal was extinguished, it’s assumed that it was either a spectacular suicide or an act of deliberate sabotage, designed to cause a train crash in revenge for being forced into early retirement.

The way stationmaster Tuszka tells it, this seems an entirely plausible course of events. From the moment they first met, he and Orzechowski never got on, and relations deteriorated when Tuszka replaced his assistant with his own protegé Zapora, whom Orzechowski regards as a spy. Things came to a head during a mass meeting when Orzechowski flatly refused to go along with a planned economy drive that would involve running the trains on inferior quality coal. In Tuszka’s version of events, Orzechowski is the physical embodiment of the forces that hold back progress.

But when Zapora and Sałata, the two other members of Orzechowski’s team, are grilled, they build a more rounded portrait of a man who, while nobody’s idea of a congenial companion, is nonetheless clearly more complex than Tuszka’s dismissive impression would suggest. And as their versions of events are dramatised in flashback, it becomes increasingly clear that for all Orzechowski’s surface unpleasantness (he’s a stickler for procedure and protocol, doesn’t suffer fools gladly, and ranks the well-being of his locomotive considerably higher than that of its human operators), he is ultimately more victim than villain.

In the year when Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s crimes sent shockwaves around the world, Andrzej Munk and his writer Jerzy Stefan Stawiński (who also wrote the novel on which Andrzej Wajda based his film Kanał the following year) offered a subtle parable of how easy it is to jump to conclusions and damn without evidence. They also offer an explicit critique of collective action that would have been unthinkable until very recently – Orzechowski’s “crime” is to be too wedded to the notion of delivering the best possible service in an environment where five-year plans and targets reign supreme. Though Orzechowski is a conservative traditionalist, and the film becomes increasingly sympathetic towards him, it’s not in any sense an anti-Communist film – rather, Munk’s position is like that taken by Mateusz Birkut, the fictional Stakhanovite bricklayer protagonist of Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble (Człowiek z marmuru, 1976), who also turns out to be a truer socialist than those who profess to represent the ideology in positions of power. Tuszka in particular is rapidly exposed as a grudge-bearing opportunist who is only too happy to compromise his own principles in order to toe the party line and secure his own advancement.

The drama is more psychological than visceral, though Munk pulls off three impressive set-pieces in the opening near-crash, an elaborate bit of fare-dodging by Zapora (who dodges inspectors by clinging to the doors outside the moving train), and a sequence in which Zapora repairs the locomotive while it’s in motion, to score points off Orzechowski. Though perhaps the most impressive bit of narrative rug-pulling comes towards the end, when Munk shows us the real reason for the problems with the lamp. Though this is nominally part of Sałata’s story, he doesn’t witness it himself, as he’s momentarily distracted, and it’s only thanks to an astute member of the railway investigation committee putting two and two together that the correct verdict on Orzechowski’s actions is finally reached.

Working largely with his regular documentary team, Munk makes good use of his experience working with trains in the earlier, very different 1953 documentary The Railwayman’s Word (Kolejarskie słowo). Romuald Kropat is once again the cinematographer and Jadwiga Zajiček the editor, and they both create a powerful sense of a world dominated by giant and impersonal machines: there’s scarcely a shot that doesn’t feature a steam train. This is further emphasised by Józef Bartczak’s soundtrack, which plays out to a constant background of clanking machinery and hissing whistles, an effect enhanced by the total absence of music.

The performances are generally excellent, with Kazimierz Opaliński and Zygmunt Listkiewicz outstanding as the rivals Orzechowski and Zapora. Two scenes underscore the subtlety of Munk’s direction and Opaliński’s performance – when Orzechowski meets and reminisces with an old friend, and when he accidentally encounters Zapora in a park on their day off, treating him with impeccably old-fashioned courtesy and charm as though their daily power-struggles had never happened. And it’s not the least aspect of Munk’s considerable achievement that he ends up treating Orzechowski – a character who could easily have remained the crude archetype peddled by Tuszka – with equal courtesy. Munk was presumably not blind to the irony that he would have to turn to fiction in order to tell something closer to the truth – Krzysztof Kieślowski would make the same discovery over two decades later.

- Director: Andrzej Munk

- Script: Andrzej Munk, Jerzy Stefan Stawiński, based on a story by Stawiński

- Camera: Romuald Kropat

- Production Design: Roman Mann

- Editing: Jadwiga Zajiček

- Sound: Józef Bartczak

- Costumes: Halina Krzyżanowska

- Production Manager: Wilhelm Hollender

- Production Company: Zespół Filmowy Kadr

- Cast: Kazimierz Opaliński (Władysław Orzechowski), Zygmunt Maciejewski (Tuszka), Zygmunt Zintel (Witold Sałata), Zygmunt Listkiewicz (Stanisław Zapora), Roman Kłosowski (Marek Nowak), Kazimierz Fabisiak (Konarski), Ludosław Kozłowski (Karaś), Janusz Bylczyński (Warda), Stanisław Marzec-Marecki (party secretary), Józef Para (railwayman), Stanisław Jaworski (Franek), Celina Klimczak (Zofia Sałata), Natalia Szymańska (Orzechowski’s wife), Józef Nowak (Jankowski), Janusz Paluszkiewicz (Krokus), Leon Niemczyk (passenger – uncredited)

DVD Distribution: There are two DVD releases of Man on the Tracks, though the apparent absence of subtitles on the Polish edition (Best Film Co, Region 0 PAL) means that the only viable option for non-Polish speakers is Polart’s edition (Region 0 NTSC).

DVD Distribution: There are two DVD releases of Man on the Tracks, though the apparent absence of subtitles on the Polish edition (Best Film Co, Region 0 PAL) means that the only viable option for non-Polish speakers is Polart’s edition (Region 0 NTSC).

Picture: By the standards of this variable label, this wasn’t at all bad, if hardly demonstration quality. The source print is a little battered, and some shots are greyer than others, but on the whole Romuald Kropat’s black-and-white photography comes across well, and the 4:3 aspect ratio appears to be correct. Although it’s a PAL-to-NTSC transfer, the drawbacks are nowhere near as pronounced as they were with Polart’s edition of Andrzej Wajda’s Innocent Sorcerers – there’s a bit of motion judder at times, but it’s easy enough to tune out.

Sound: Typical 1950s mono, but entirely adequate for the purpose, and with no audible flaws worth noting.

Subtitles: A pleasant surprise. Although there are a couple of typos, and they occasionally spill over onto three lines, these are minor niggles compared with the fact that they’re white, clear, idiomatic, properly synchronised and optional.

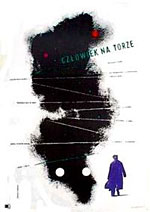

Extras: The only extras are a short text biography of Munk, a filmography, and a copy of Stanislaw Zamecznik’s original poster from 1957 (which, like most Polish film posters, is a work of art in its own right, and is reproduced at the top of this piece). ‘Also Available’ links to cover scans of other Polart releases, but no trailers or other video material.

Links

- YouTube has an extract from the middle of the film, albeit in unsubtitled Polish.

- Filmpolski.pl (in Polish)

- Internet Movie Database

- Reviews: Critical Culture (Pacze Moi); Dennis Grunes; Strictly Film School (Acquarello); Ozu’s World (Dennis Schwartz)

- Two articles on Munk, from Culture.pl and Film Comment (Stuart Klawans), both discuss Man on the Tracks in the context of the rest of his work.

- DVD available from: Amazon.com; DVD Empire; Polart.com